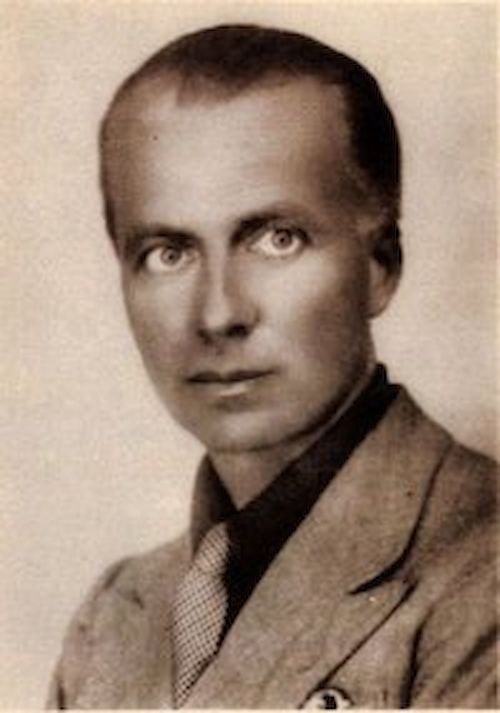

Giacinto Scelsi: Sound Messenger 1905-1988

Dary John Mizelle on Scelsi

-How did you meet Scelsi?

I was in Italy in ‘74, and I had heard about S– back in the 60’s…S– had already begun using the one note concept, and to hear it described, I had really no idea what it would be like; I had heard a woodwind quartet by Elliot Carter in which one movement was all one note, and I thought maybe it would be like that; then I went there in ‘74 and I had a friend in Rome who was acquainted with S–, and we had a multiphonic vocal group called Prima Materia. We played some gigs around Italy and I went to Rome for a while and G.S. was like the godfather of this group. Michiko Hirayama, who was his close associate for many years, was in the group and when I got there, Michiko and I became really good friends, and then S– and I became good friends too. He took an interest in me and my work, he liked what I was doing in the group and we would rehearse in his apartment once in a while. His apartment was in a really interesting place because it was right in the middle of the divide between the ancient roman forum and the modern city. He would take us up on his penthouse…he was a wealthy man, I guess, evidently he was related to a Sicilian count, though it never came up in conversation. I know he had friends that were famous artists, and he had an original Salvador Dali hanging on his wall and I think he was friends with Marcel Duchamp. At one point we traded tapes and one of the things he sent me was Duchamp speaking.

-Were you familiar with Scelsi’s improvisatory method of composing at that time?

The story was that he would go up on the penthouse and sit and meditate and that he was trying to reinvent music and reinvent himself, because he had been quite ill. He told me that he had some kind of a nervous disorder, which in his opinion was caused by writing too much serial music. He was a very high-strung sort of guy. In order to cure himself–he said that he had visited 160 doctors and nobody could help him–so in order to cure himself he decided he had to reinvent himself and reinvent music so that he could compose in such a way that would not cause him such nervous harm. And he came up with this method where he would meditate up on his penthouse and then after he was through meditating, he would improvise on a small electronic keyboard instrument. He would tape these improvisations and then would transcribe those into his compositions. He had a lot of help from Michiko Hirayama and other people with the notation, especially Michiko who would interpret changes of timbre to mean changes of vowel. He offered me a job doing transcribing in ‘74 but I wasn’t able to do it. He was such a strong personality, he reminded me a bit of Stockhausen in the strength of his personality. I knew that if I got involved as an assistant I would probably lose something of my own personality towards working on my own work, at least temporarily and it wasn’t really a practical concern anyway. There was a whole circle of people around him many of who were quite creative including Michiko, Alvin Curran who was living in Rome at the time and the performers Giancarlo Scaffini, the trombonist, and Frances Marie-Uitti, the cellist.

-Scelsi’s improvisation method seemed to involve putting himself in an altered state; especially one arrived at by Yogic meditation. Did he ever talk to you about that?

S-– had a way of getting back to what he considered to be the primal vibration that was the original impulse for music. He practiced yogic meditation and he had ideas about the Kundalini chakra, which starts at the base of the spine and then unfolds through the body via the sushumna nadi, or central nervous system. His ideas about performance involved making that energy move and manifesting through an instrument. I remember him saying one day in passing that a new way to learn how to play the piano would be to concentrate on the base of the spine and then think of a note on the keyboard, with your eyes blindfolded, and then just go from that impulse to that note, then do that for all 88 keys so you would have a way of playing not in melodic contexts where one note is connected to another by a phrase, but they would all be connected by through this movement of energy from the base of his spine. That was actually the impulse for performing the vocal music in Prima Materia. It was originally begun as an experimental approach to finding vocal multiphonics but because of the interest in our group in yoga and meditation, it became something different in that it involved multiphonic production but it also became a sense that the music was flowing from a common primal source rather than improvised music, which is action and reaction. One of the things we would always do is after having performed we would invite an audience to sing with us and it usually went quite well because of the aura that was created by the first performances. There was quite a following for that group in Europe.

-So Scelsi’s music was alive and flourishing, even popular in Europe during the 70’s.

Absolutely.

-There are some people who think that Scelsi was a loner, and stayed aloof from the musical scene of his day, but we now know that to be a rumor. He was in fact intensely involved with the performers who played his work, and that can be attested to by his idiomatic writing style.

I remember one time speaking to Luciano Berio about Scelsi and he said something to the effect that “oh, he’s just and old man…there’s not much music happening…” I don’t think Berio was too interested in experiencing S–’s world, being a more cosmopolitan international composer.

-Scelsi can be considered an extreme non-rational composer. How would you compare his work to a rationalist such as Xenakis?

I like the hardheaded rationality of Xenakis’ music but I could also recognize that there was something going on outside of that. Xenakis’ original impulse came from ancient Greek philosophies. He talked about people like Xeno and Parmenides, and the Pre-Socratics. I think Scelsi’s original impulse for his work at least the post-serial work was from India. They say in the ancient world, 5000 years or so ago, there were three main seats of civilization, Egypt & Mesopotamia from which Greek culture evolved from, and India and China.

-Xenakis manifests the Egyptian/Mesopotamian seat, Scelsi the Indian, and perhaps John Cage the Chinese?

Yes- Cage was certainly steeped in Chinese philosophy, and applied the I Ching to his compositions.

-Composers who deny rationality always face great resistance, but Scelsi seemed to wholeheartedly adopt the non-rationalist view, referring to himself not as a composer but a messenger.

For Scelsi, I know that it took a huge act of courage on his part to abandon rationality. European culture has such a tight control of the feelings through rationality, you look at the tradition of Beckett, Kafka, Sartre, and Kierkegaard for example, there’s like almost a glory in pain and anxiety because its so full of thought power, So for Scelsi to give all that up, all that rationality, well it was a very practical solution for him because his health had failed him. He had to find something to be able to keep alive and working. I think his solution was quite an original one at least in the context of contemporary Europe, and he lived for a long time after that.

-After you returned to the states, did you know of or hear of performances of Scelsi’s work here?

I think he was getting performed in San Diego and San Francisco, though I don’t remember who was doing it.

-Any final thoughts?

Scelsi’s biggest influence on me was how he got away from polyphony and gone back to a certain monophonic voice, even when it was full of different instruments and voices, they were all speaking with the same voice rather than contrapuntally. Harmony wouldn’t exist; instead there would be a unified expansion of sound into complex timbre and sound masses.

-Like going into the “interior of the sound”?

Exactly.

- Giacinto Scelsi: Sound Messenger 1905-1988

- Dary John Mizelle on Scelsi